HTN SPONSORED BUSINESSES

DONATE TO KEEP THE MOVEMENT GOING

J W's Album: Wall Photos

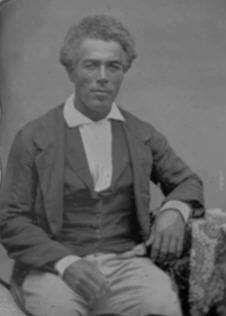

Horace King......

Horace King (sometimes Horace Godwin) (September 8, 1807 – May 28, 1885) was an African-American architect, engineer, and bridge builder.[1] King is considered the most respected bridge builder of the 19th century Deep South, constructing dozens of bridges in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi.[2] In 1807, King was born into slavery on a South Carolina plantation. A slave trader sold him to a man who saw something special in Horace King. His owner, John Godwin taught King to read and write as well as how to build at a time when it was illegal to teach slaves. King worked hard and despite bondage, racial prejudice and a multitude of obstacles, King focused his life on working hard and being a genuinely good man. King built bridges, warehouses, homes and churches.

Horace King was born into slavery in 1807 in the Cheraw District of South Carolina, in present-day Chesterfield County. King's ancestry was a mix of African, European, and Catawba.[4] Mid-20th century biographer F. L. Cherry described his complexion as showing more "Indian blood than any other."[5] Taught to read and write at an early age, he had become a proficient carpenter and mechanic by his teenage years.[6]

Records indicate King spent his first 23 years near his birthplace, with his first introduction to bridge construction in 1824.[7] In 1824, bridge architect Ithiel Town came to Cheraw to assist in the construction of a bridge over the Pee Dee River.

When King's master died around 1830, King was sold to John Godwin, a contractor who also worked on the Pee Dee bridge.[9] King may have been related to the family of Godwin's wife, Ann Wright.[4] In 1832, Godwin received a contract to construct a 560-foot (170 m) bridge across the Chattahoochee River from Columbus, Georgia to Girard, Alabama (today Phenix City). Initially living in Columbus, he moved to Girard in 1833, taking King with him.[10] The pair began many other construction projects, including house building. They built Godwin’s house first, then King’s. This was followed by many speculative houses, and the two men completed nearly every early house in Girard. The Columbus City Bridge was the first known to be built by King, who likely planned the construction of the bridge and managed the slave laborers... During a time of financial difficulty, in 1837 Godwin transferred ownership of King to his wife and her uncle, William Carney Wright of Montgomery, Alabama. This may have been done to protect King from being taken and sold by Godwin's creditors.[4] King was allowed to marry Frances Gould Thomas, a free woman of color, in April 1839. It was extremely uncommon for slave owners to allow such marriages, since Frances' free status meant that their children would all be born free.[4] Slave states had incorporated the principle of partus sequitur ventrem into law since the colonial period, which said that children took the social status of their mothers, whether slave or free.

By 1840, King was being publicly acknowledged as being a "co-builder" along with Godwin, an uncommon honor for a slave.[13] King's prominence had eclipsed that of his master by the early 1840s. He worked independently as architect and superintendent of major bridge projects in Columbus, Mississippi (1843) and Wetumpka, Alabama (1844).[4][11] While working on the Eufaula bridge, King met Tuscaloosa attorney and entrepreneur Robert Jemison, Jr., who soon began using King on a number of different projects in Lowndes County, Mississippi, including the 420-foot (130 m) Columbus, Mississippi bridge. Jemison would remain King's friend and associate for the rest of his life.[14] King bridged the Tallapoosa River at Tallassee, Alabama in 1845. Later that same year he built three small bridges for Jemison near Steens, Mississippi, where the latter owned several mills.....Despite his enslavement, King was allowed to keep a significant income from his work. In 1846, he used some of his earnings to purchase his freedom from the Godwin family and Wright. But, under Alabama law of the time, a freed slave was allowed to remain in the state only for a year after manumission. Jemison, who served in the Alabama State Senate, arranged for the state legislature to pass a special law giving King his freedom and exempting him from the manumission law. In 1852, King used his freedom to purchase land near his former master.[15] When Godwin died in 1859, King had a monument erected over his grave....

King left the Alabama Legislature in 1872 and moved with his family to LaGrange, Georgia. While in LaGrange, King continued building bridges, but also expanded to include other construction projects, specifically businesses and schools. By the mid-1870s, King had begun to pass on his bridge construction activities to his five children, who formed the King Brothers Bridge Company. King's health began failing in the 1880s, and he died on May 28, 1885 in LaGrange.[24]

King received laudatory obituaries in each of Georgia's major newspapers, a rarity for African Americans in the 1880s South. He was posthumously inducted into the Alabama Engineers Hall of Fame at the University of Alabama. The award was accepted on his behalf by his great-grandson, Horace H. King, Jr.[25] He was remembered both for his engineering skill and for his character.

Horace King (sometimes Horace Godwin) (September 8, 1807 – May 28, 1885) was an African-American architect, engineer, and bridge builder.[1] King is considered the most respected bridge builder of the 19th century Deep South, constructing dozens of bridges in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi.[2] In 1807, King was born into slavery on a South Carolina plantation. A slave trader sold him to a man who saw something special in Horace King. His owner, John Godwin taught King to read and write as well as how to build at a time when it was illegal to teach slaves. King worked hard and despite bondage, racial prejudice and a multitude of obstacles, King focused his life on working hard and being a genuinely good man. King built bridges, warehouses, homes and churches.

Horace King was born into slavery in 1807 in the Cheraw District of South Carolina, in present-day Chesterfield County. King's ancestry was a mix of African, European, and Catawba.[4] Mid-20th century biographer F. L. Cherry described his complexion as showing more "Indian blood than any other."[5] Taught to read and write at an early age, he had become a proficient carpenter and mechanic by his teenage years.[6]

Records indicate King spent his first 23 years near his birthplace, with his first introduction to bridge construction in 1824.[7] In 1824, bridge architect Ithiel Town came to Cheraw to assist in the construction of a bridge over the Pee Dee River.

When King's master died around 1830, King was sold to John Godwin, a contractor who also worked on the Pee Dee bridge.[9] King may have been related to the family of Godwin's wife, Ann Wright.[4] In 1832, Godwin received a contract to construct a 560-foot (170 m) bridge across the Chattahoochee River from Columbus, Georgia to Girard, Alabama (today Phenix City). Initially living in Columbus, he moved to Girard in 1833, taking King with him.[10] The pair began many other construction projects, including house building. They built Godwin’s house first, then King’s. This was followed by many speculative houses, and the two men completed nearly every early house in Girard. The Columbus City Bridge was the first known to be built by King, who likely planned the construction of the bridge and managed the slave laborers... During a time of financial difficulty, in 1837 Godwin transferred ownership of King to his wife and her uncle, William Carney Wright of Montgomery, Alabama. This may have been done to protect King from being taken and sold by Godwin's creditors.[4] King was allowed to marry Frances Gould Thomas, a free woman of color, in April 1839. It was extremely uncommon for slave owners to allow such marriages, since Frances' free status meant that their children would all be born free.[4] Slave states had incorporated the principle of partus sequitur ventrem into law since the colonial period, which said that children took the social status of their mothers, whether slave or free.

By 1840, King was being publicly acknowledged as being a "co-builder" along with Godwin, an uncommon honor for a slave.[13] King's prominence had eclipsed that of his master by the early 1840s. He worked independently as architect and superintendent of major bridge projects in Columbus, Mississippi (1843) and Wetumpka, Alabama (1844).[4][11] While working on the Eufaula bridge, King met Tuscaloosa attorney and entrepreneur Robert Jemison, Jr., who soon began using King on a number of different projects in Lowndes County, Mississippi, including the 420-foot (130 m) Columbus, Mississippi bridge. Jemison would remain King's friend and associate for the rest of his life.[14] King bridged the Tallapoosa River at Tallassee, Alabama in 1845. Later that same year he built three small bridges for Jemison near Steens, Mississippi, where the latter owned several mills.....Despite his enslavement, King was allowed to keep a significant income from his work. In 1846, he used some of his earnings to purchase his freedom from the Godwin family and Wright. But, under Alabama law of the time, a freed slave was allowed to remain in the state only for a year after manumission. Jemison, who served in the Alabama State Senate, arranged for the state legislature to pass a special law giving King his freedom and exempting him from the manumission law. In 1852, King used his freedom to purchase land near his former master.[15] When Godwin died in 1859, King had a monument erected over his grave....

King left the Alabama Legislature in 1872 and moved with his family to LaGrange, Georgia. While in LaGrange, King continued building bridges, but also expanded to include other construction projects, specifically businesses and schools. By the mid-1870s, King had begun to pass on his bridge construction activities to his five children, who formed the King Brothers Bridge Company. King's health began failing in the 1880s, and he died on May 28, 1885 in LaGrange.[24]

King received laudatory obituaries in each of Georgia's major newspapers, a rarity for African Americans in the 1880s South. He was posthumously inducted into the Alabama Engineers Hall of Fame at the University of Alabama. The award was accepted on his behalf by his great-grandson, Horace H. King, Jr.[25] He was remembered both for his engineering skill and for his character.

No Stickers to Show