HTN SPONSORED BUSINESSES

DONATE TO KEEP THE MOVEMENT GOING

J W's Album: Wall Photos

General Godfrey Weitzel, who commanded the Union troops entering Richmond, later recalled: “There was some dispute as to which troops first entered Richmond, white or colored. As there was no fighting in going in I did not consider it of much consequence. ..Maj. Emmons E. Graves, senior aide-de-camp on my staff, in command, with Maj. Atherton H. Stevens, J., and about forty men of the 4th Massachusetts Cavalry were the first to enter.”3 Jay Winik wrote in April 1865:

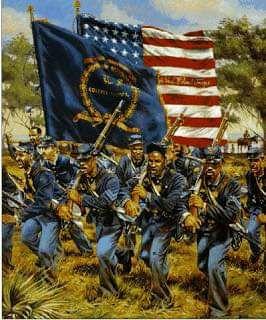

As white Richmond retreated behind shutters and blinds, black Richmond spontaneously took to the streets. From the moment Union troops entered the city – ‘Richmond at last!’ Black Union cavalrymen shouted – crowds, the skilled and the unskilled, household servants and household cooks, rented maids and hired millworkers, jammed the sidewalks to catch a glimpse of the spectacle. No longer enslaved, they thrust out their hands to be shaken or presented the soldiers with offerings: gifts of fruit, flowers, even jugs of whiskey. Federal officers riding alongside promptly reached for the liquor bottles and smashed them with their swords. But the crowd was undaunted. Just a day earlier, they had been prohibited from smoking, publicly swearing, carrying canes, purchasing weapons, or procuring ‘ardent spirits.’ Yet now, to the sounds of ‘John Brown’s Body,’ they jubilantly waved makeshift rag banners; to the tune of the ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic,’ they enthusiastically hugged and kissed the bluecoats. For hours, ignoring the furnacelike heat and the smoke-choked air, they lingered in the dusty streets as Federal soldiers passed, bowing and giving thanks (‘de Yankees at last has gone and cum!&rsquo . In the late morning, when black troops marched in lockstep (‘majestically and proudly defiant,’ in the words of an onlooker), the danced with unimpeded joy. And most of all, they praised God, shouting ‘hallelujah.’ Recalled on Connecticut soldier, ‘Our reception was grander and more exultant than even a Roman emperor…could ever know.'”4

. In the late morning, when black troops marched in lockstep (‘majestically and proudly defiant,’ in the words of an onlooker), the danced with unimpeded joy. And most of all, they praised God, shouting ‘hallelujah.’ Recalled on Connecticut soldier, ‘Our reception was grander and more exultant than even a Roman emperor…could ever know.'”4

As white Richmond retreated behind shutters and blinds, black Richmond spontaneously took to the streets. From the moment Union troops entered the city – ‘Richmond at last!’ Black Union cavalrymen shouted – crowds, the skilled and the unskilled, household servants and household cooks, rented maids and hired millworkers, jammed the sidewalks to catch a glimpse of the spectacle. No longer enslaved, they thrust out their hands to be shaken or presented the soldiers with offerings: gifts of fruit, flowers, even jugs of whiskey. Federal officers riding alongside promptly reached for the liquor bottles and smashed them with their swords. But the crowd was undaunted. Just a day earlier, they had been prohibited from smoking, publicly swearing, carrying canes, purchasing weapons, or procuring ‘ardent spirits.’ Yet now, to the sounds of ‘John Brown’s Body,’ they jubilantly waved makeshift rag banners; to the tune of the ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic,’ they enthusiastically hugged and kissed the bluecoats. For hours, ignoring the furnacelike heat and the smoke-choked air, they lingered in the dusty streets as Federal soldiers passed, bowing and giving thanks (‘de Yankees at last has gone and cum!&rsquo

No Stickers to Show